- Home

- Daniel Nieh

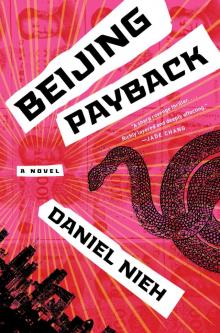

Beijing Payback Page 12

Beijing Payback Read online

Page 12

“Yeah.” I accept the business card and put it the pocket of my shorts. “Same page.”

He smiles and sits back into the booth. “Good. I thought so. Let’s get out of here.”

Lang takes a peppermint from the basket on the host stand as we walk out. “All right, honey, you have a nice day,” the hostess calls out to him, and, without turning his head, he waves the back of his hand over his shoulder. Out in the parking lot, he beeps us into a gold Buick, an incognito cop car which nonetheless has three or four giant antennae mounted on the chassis.

Lang pops the peppermint into his mouth and slips the plastic wrapper into his shirt pocket. Then he starts the car, backs out of his parking spot, and noses the Buick gently out onto Arrow Boulevard. After a minute or two of silence, he punches on the radio, which assaults our ears with a bubblegum pop tune about having both a new car and a new girlfriend at the same time.

It’s a song I might have sung in the shower two weeks ago, but now the lighthearted melody strikes a violent contrast with the scene in my head: a faceless woman with a huge belly, biting her lip as she hands her passport to an immigration official. All in order to bring her unborn baby to that clean, light place that she’s seen on a movie screen. We drive past Daily Donut, we drive past Vapor Bliss. We drive past San Dimas Pet Resort and Grooming Spa. And then I decide to shut my eyes.

* * *

Cain’t nobody hold these niggas down

No doubt

Bringin’ bad boys into ya town

Make ya shout

Comin’ at ya with the freshest flavas

No doubt

Tell ya aunties tell ya cousins tell ya neighbas

Make ya shout

Sun and Andre are sitting forward on the sofas, elbows on their knees, the remnants of a bagelwich run strewn around the coffee table. Sun’s head is cocked to the side as he tries to catch the lyrics to the chorus of one of Regime Change’s clubbier tracks.

“Nice sound, but I am not understand too much,” Sun admits.

“Makes you want to dance, though, right?” Andre holds his arms out, elbows in, and shimmies his shoulders. Sun laughs shyly. Andre laughs with him and then slumps back into the sofa. “That’s the old-school sound. They don’t make them like that anymore.”

Sun moves the stereo jack from Andre’s phone to his own.

“My favorite song is also old-school sound,” he says, putting on “Man in Black.”

“No way. How do you know about Johnny Cash?”

Sun indicates me with his chin. “His father.”

Andre turns around and sees me just inside the door.

“Damn, Victor! How long’ve you been lurkin’ there like a straight-up creeper?”

“I’ve gotta pick my classes,” I say, slipping into my room. I nudge the door closed with my foot and pull my laptop into bed with me.

ECON 301: Fiscal Policy and Sovereign Debt. BPUB 240: International Markets in the Twenty-First Century. EAS 322: Newspaper Chinese. Can I enroll in Marketing 202 if, due to my father’s gruesome assassination at the hands of his former blood brothers, I have not yet taken the final for Marketing 201? I guess I’d have to talk to Shellie in the Dean’s Office about that. Maybe I should take statistics and finally get that Quantitative Data Analysis requirement out of the way. I did what I had to do in order to survive. MATH 105: Business Statistics. Tuesdays and Thursdays at 8:00 A.M. I could still make the first lecture tomorrow morning.

Someone taps on my door. I sit up on the bed, put the laptop aside, and say, “Come in.”

Sun pads in in his socks and sits cross-legged on the floor.

“Did you read the letter?” he asks.

“Yes,” I say. “Have you?”

“I transcribed it,” he says. “Old Li asked me to when he visited Beijing in October. That was the last time I saw him. He told me you could not read handwritten Chinese.”

I feel a blush suggest itself around the edges of my face. “Then why didn’t you tell me that my sister wasn’t supposed to read it?”

Sun cocks his head to one side. “I didn’t think anything I could say would stop her from seeing it. Lianying was never supposed to be involved. In October, Old Li did not mention that you couldn’t drive.”

“The DUI happened in November.” The blush deepens. “You two weren’t, like, texting about this or anything?”

“No.”

We sit like that for a minute or two. Then I say, “It just doesn’t make sense to me. Why would he lie about these things for his whole life and then ask me to get involved after he’s dead?”

Sun is studying a bruise on his wrist that he must have acquired during the break-in to Happy Year. I notice for the first time how strong and sinewy his arms are.

“I wondered the same thing,” he says. “So I asked him. He said to me that you’re very capable, you can handle the challenge. He said that I’d be able to keep you safe.”

“And you agreed?”

He glances up from his bruise, looks at me.

“Yes, I agreed,” Sun says. “But I think he was not willing to admit the main reason he chose you to come with me.”

“Which is?”

“Old Li didn’t have anybody else he could count on.”

I let this sink in for a moment, try to put myself in Dad’s shoes: an unbearably lonely proposition. A single father with a double life, running four restaurants, a remittance business, and a citizenship racket. Dad didn’t really have close friends, just a few restaurant buddies he played cards with on Monday nights. His life was work and family. Who could he ask to avenge him?

Sun says, “I understand your hesitation. I can’t make you go. Maybe if I were you, I wouldn’t. And to be honest, I prefer to work alone. But this time I can’t.”

“Why not? How do I fit into this plan, anyway?”

“You just have to be the face,” Sun says. “If I go back to Beijing and start trying to buy information on Ouyang and Zhao, I might be dead within twenty-four hours. But nobody knows who you are. Old Li made sure of that. He never let any of his brothers visit him in the United States. And since you’re an American, you can have access where I cannot.”

“I never would have thought that revenge would be so important to him,” I say.

“I think if Old Li were here,” Sun says, “he would say we can make up for past mistakes.”

I’m staring out the window at the row of fan palms in the center of the Quad, swaying slightly in the winter wind. Fiscal Policy and Sovereign Debt. Dad was good at making you feel special.

“Think it over,” Sun says, rising to his feet. He quietly pulls the door shut behind him.

I pull my laptop back into my lap and open a new tab, search for “organized crime in China,” and click through to a list of Chinese gangs and Triad societies. The Continentals, the Green Dragons, the Kit Jai. Criminally influenced tongs—what’s a tong? I click through more links. The feud between Street Market Wai and Broken Tooth Wan. “The number of people involved in organized crime on the mainland rose from around 100,000 in 1986 to 1.5 million in the year 2000.” I look up San Dimas crime statistics on a public database and discover that, on average, there are zero murders here annually. Robberies, petty theft, vagrancy. Detective Richard Lang, firm, calm, and affable, was just the man for the job. Except maybe for this one case.

I do another search and turn up Dr. Aron Ancona’s office number at Cedar Sinai. The phone rings seven or eight times, and just when I’m about to give up, a heavy voice comes on the line and says hello.

“Yes, hi, Dr. Ancona. My name is Victor Li? Vincent Li was my father?”

The line is quiet for a while. “Who was your father?” he asks.

“Vincent Li?”

“I’m afraid I don’t know anyone by that name.”

I grit my teeth, and for some reason Jason Maxwell pops into my head, backing me down, lowering his shoulder.

“So you’d be pretty surprised if I told you that he was mur

dered and your address was found among his things?”

“My goodness, yes.” The heavy voice takes on a troubled, sympathetic tone. “Yes, I’m afraid it would be a complete surprise.”

Pinching the phone between my shoulder and my ear, I pull open the drawstring to Sun’s backpack. Black T-shirts, black jeans, black socks, little black drill. Envelopes of more U.S. and Chinese cash. Chinese bank cards and credit cards in a black vinyl wallet. I wear the black in mourning for the lives that could have been.

Dr. Aron Ancona clears his throat. “If there’s something I can help you with—”

“Hey, yeah, right. You didn’t know him, you said. So you wouldn’t mind if I shared that detail about your address with the police who are investigating his murder?”

There’s another long pause, and when the heavy voice comes back, all the concern is gone.

“Look, kid, I don’t know what you think you’re doing, but you’re barking up the wrong tree. Your dad and I were involved in a business deal and he backed out. I found someone else to work with. End of story. Okay? If he got himself killed it’s got nothing to do with me, so you can tell the cops whatever the fuck you want.”

“What kind of business deal? Was it ketamine? Was it Ice?” I’m asking, but he has already hung up.

“What the fuck kind of business deal?” I say it again to the ceiling, then punch the palm of my right hand hard, twice. I snatch the basketball out of my gym bag, snap it back and forth in my fingertips. I count down two or three shot clocks: pick and pop, high-low, flare off the screen for the jumper. A Russian dealmaker named Feder Fekhlachev. Business Statistics, Tuesdays and Thursdays, 8:00–10:00. Practice at 4:30. Another day as an econ major and backup point guard. You must help repay that debt. I replay Sun’s precise plan at Happy Year: the decoy, the ambush, the flashing kicks. Why did Dad lock the letter in the restaurant safe instead of leaving it at Chateau Happiness with the gun and the passport? Can you believe it’s SDSO standard issue now? The dearth of certainty roars in my head, unignorable, like a vacuum cleaner.

I put down the ball and dig further into Sun’s backpack. In a side pocket, I find a pair of photographs. One is cropped from a team portrait on the SDSU Athletics website: me in my basketball jersey and a toothy grin, the clueless boy Sun crossed the ocean to locate and retrieve. The other is a worn film print at least a dozen years old: Dad in his signature starched white shirt, sleeves cuffed, one long arm draped over Sun’s teenage shoulders. They are standing on a beach somewhere in China, flashing grins of their own, the sun casting long shadows on the coarse, seaweed-strewn sand behind them.

Why did Sun show me the monkey figurine and not this?

I should stay. I should enroll in classes. I should never find out the answer to that question.

I put the photographs back and pick up the drill, examine it in my hands. He was completely two-faced and deceitful. It’s a remarkable piece of engineering, all smooth lines and matte finish. There’s no branding or logo on it, only some Japanese writing on the handle. She will try to stop you. In my hands the drill is compact and heavy, like a weapon.

Part Two

People’s Republic of China

18

I like long plane trips because they restrict your freedom. All your choices of potential actions melt away, and all that’s left is time—time to work through the backlog of thoughts and anxieties crowding your mind until nothing’s left, and you just tilt your head back and gaze in blissful boredom out at the world floating past. The flight from LAX to Beijing is about twelve hours, which gives me plenty of time to ponder how Jules, Andre, and Coach Vaughn will react to the notes I left for each of them; how long it will take Lang to find out that I’ve left the country; whether or not I’m a complete fucking idiot; and so on. There isn’t anything I can do about any of it on this plane, which is a relief. Actions were taken by a younger Victor, and will soon be taken by an older Victor, but in the air, all this Victor can do is sit here thinking stuff over and eating pretzels.

Sun’s story of greed and conspiracy had barely dented the trance I’d been walking around in since Dad’s death, but his precise burst of violence at the restaurant woke me up like a glass of ice water to the face. Nothing about his personality led me to expect him to knock out an armed security guard with brutal economy. But then I realized that I’d appraised him through the same biased glasses that our society has leveled at Chinese-Americans from Michael Chang to Jeremy Lin: he’s small, he’s polite, so he’s probably not a badass. It was the sort of superficial judgment that I had to defy every time I stepped on the basketball court.

Dad had never minded being misjudged in this way. He probably saw it as an advantage: a benign disguise that helped him conceal his backdoor dealings, past and present. But now that I had an idea of what was going on, I wouldn’t be satisfied with skating along the surface anymore. I couldn’t send Sun back to China and go back to basketball practice like nothing had happened, knowing my world only through a glass, darkly. Ice: the frozen form of the source of all life, a shelf in the Antarctic, a volatile commodity, a smuggling operation that had cost Dad his life. Glass: both a liquid and a solid, two opposed ideas at the same time. Perfectly hard, ostensibly clear, yet it can be stained, soiled, distorted. And one good scratch could destroy its integrity; one well-thrown Bible could shatter the barrier between two realms, previously compartmentalized.

I attempted to reconstruct Dad’s letter a few times on the plane, tried to organize my thoughts around all the new information. Dad had started a new life by leaving China and opening the restaurants, but Zhao and Ouyang insisted that he help them from his position in the States. When he fought back against their plan to import ketamine, they sent Rou Qiangjun to take over the U.S. operations. And Dad, like the clever crook I guess he always was, had anticipated all of it with a contingency plan: Sun would come collect me from San Dimas, and the two of us would travel to Beijing to shut down Happy Year for good.

But was Rou the killer, or just the replacement? And what about that first break-in at the restaurant that he mentioned—was that just a disgruntled employee making a cash grab? Then there were Aron Ancona and the lawyer, Peng—I have no idea where they fit in. When I think back to my brief, testy phone conversation with Ancona, my jaw clenches until my crowned molar starts aching. I’m sick of people patronizing me and hiding behind lies. Maybe Dad didn’t have much of a choice. But I’m not going with Sun just because Dad wanted me to. I took Jules’s advice, thought about it rationally, made my own decision. I need some answers to the questions that are pinching my brain like clothespins.

And then a moment comes when we fly over a break in the sea of marshmallow fluff and I glimpse the vastness of the Pacific Ocean toiling away below, the biggest damn thing on the planet, and it strikes me how absurd it is for me to be hurtling over it in a metal tube—when did traversing an ocean become such a casual thing?—and even though I haven’t felt like breathing in a week, I wonder whether the hard part is just beginning.

Speaking with Sun so much over the past few days, my Mandarin has gotten a lot smoother. My tones have always been good, but now I don’t have to focus on them—I can just talk like I’m talking, without expending so much energy listening to myself to ensure all the dips, sings, and chops are in the right places. It’s whenever a rising second tone follows a scooping third tone, like in the words for “originally” or “American dollar,” that I get tripped up the most, often mispronouncing the two syllables in one of the more common double-rising patterns for two second tones in a row, or two third tones, or a second tone followed by a third tone. A third tone to second tone word is like an unbroken two-syllable journey from the bottom of my voice to the top: běnlái, měiyuán. Then there are the ringing, level first tones and the sharp, dropping fourth tones—I mix those up sometimes, too, especially when I’m speaking quickly. In order to get it all right, I have to remember to talk at my own speed instead of trying to match the rapid-fire

pace of native speakers.

I’m keeping all that in mind as I stand in line to pass through immigration, ready to break out the answers that Sun drilled into me, but the poky, bored-looking guy in the booth doesn’t even glance up at me as he stamps my passport.

“Kàn zhèli—Look here,” he says, tapping a little camera with his index finger. I look there, he clicks his mouse, and there I go into the system.

“Next.”

We step into the immense main concourse, the strange light of Beijing streaming through endless rows of plateglass windows. The air is a dense gray, hanging around too closely to be clouds, the sun low and crimson, an unfamiliar star lent an insidious tint by the exhaust pipes of five million cars, the smokestacks of ten thousand factories, the dust storms blowing in from the Gobi Desert. The airport is a fortress of organization and filtered air; the city stretches beyond it, ocean-like in its scale, a place to conquer or vanish.

“The air has gotten a little better,” I say, dumbly.

“Yes, it has,” Sun says without glancing up from his phone. Sun has grown more tight-lipped and serious now that we’ve arrived in Beijing, probably nervous about popping up on Ouyang or Zhao’s radar. As soon as we passed customs, he slipped into the bathroom to change into his disguise: gray drawstring joggers, a smart yellow messenger jacket, and a trucker hat pulled low over his eyes. He blends in well with the hordes of suave millennial Chinese. When we came to visit as a family more than a decade ago, this massive terminal hadn’t been built yet. The old one was filled with novice travelers listing around in a daze, squinting at signage, lugging giant plaid duffel bags made of cheap vinyl. Now the air is slightly clearer and the yuppies have cleaned up nicely. Their suitcases have four wheels; their sunglasses say Givenchy; they order without glancing at the menu at Burger King, at Yoshinoya, at Jackie Chan’s Cafe.

Beijing Payback

Beijing Payback